Food & Drink

10 Native American Food Staples That Shaped Early Cuisine

Long before modern agriculture, Native American communities cultivated and harvested foods that became the foundation of early cuisine. These staples provided nourishment, influenced culinary traditions, and shaped diets that continue to have an impact today. Many of these ingredients not only stood the test of time but also laid the groundwork for some of the most enduring culinary practices—let’s explore the staples that shaped it all.

Corn Nourished Civilizations And Transformed Agriculture

Few crops have shaped history as profoundly as corn. Indigenous farmers domesticated maize over 9,000 years ago, turning it into a dietary and economic powerhouse. Its adaptability allowed it to thrive in various climates, establishing itself as a fundamental crop for numerous civilizations throughout the Americas.

Beans Strengthened Both Diets And Soil Fertility

Protein-packed and fiber-rich, beans fueled Indigenous populations and enriched the land. The Three Sisters planting method—where beans, squash, and corn grew symbiotically—created sustainable agriculture. Iroquois and Pueblo communities stewed them with venison or dried them for winter, ensuring year-round nourishment.

Squash Provided Essential Nutrients And Storage Advantages

Long-lasting, they thrived in Indigenous fields. Groups like the Cherokee and Lenape roasted its flesh over open flames or mashed it into rich soups. Its vitamin-rich seeds added protein to meals, while dried gourds served as storage containers, utensils, and even musical instruments in tribal ceremonies.

Bison Fueled Nomadic Tribes With Nutrient-Dense Meat

Great Plains tribes depended on bison for survival, using every part of the animal. Lakota and Cheyenne hunters processed its lean meat into pemmican—a high-energy food mixed with berries and fat. Bones became tools, and hides were used for shelters. Meanwhile, sinew provided durable thread for stitching.

Wild Rice Offered A Sacred And Sustainable Grain

Far from ordinary rice, this aquatic grain grew naturally in lakes and wetlands, hand-harvested by the Ojibwe and Menominee using carved wooden paddles. High in protein and minerals, wild rice paired with game meats or dried berries. Its annual harvest was celebrated through feasts and spiritual ceremonies.

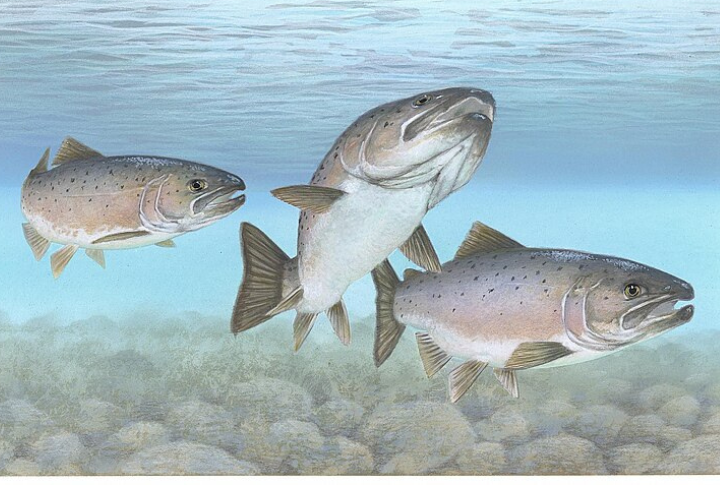

Salmon Defined Coastal Diets And Cultural Traditions

Flowing through the rivers of the Pacific Northwest, salmon sustained generations of Indigenous communities. The Chinook and Tlingit mastered techniques like smoke-drying and curing, which preserved fish for lean seasons. Tribal legends honored the salmon’s return each year and reinforced its significance beyond just sustenance.

Maple Sugar Sweetened Foods Long Before Cane Sugar Arrived

Indigenous communities such as the Anishinaabe and Algonquin harvested maple sap in early spring, slowly boiling it down to create rich syrup or crystallized sugar. It became a prized ingredient in stews, cornbread, and teas. Maple camps brought families together, blending work with storytelling and communal feasting.

Acorns Sustained Forest-Dwelling Tribes Through Harsh Winters

Beneath towering oak trees, gatherers collected acorns, turning them into a versatile food source. After leaching away tannins, the Chumash and Miwok ground them into flour for dense and nourishing bread. This slow but rewarding process turned bitter nuts into a survival staple packed with energy.

Chilies Introduced Heat And Healing To Indigenous Cooking

More than just a spice, chilies played a role in medicine and food preservation. The Pueblo and Apache dried and ground them into fiery pastes, adding depth to stews and smoked meats. Capsaicin helped boost circulation while trade routes spread bold flavors far beyond the Southwest.

Sunflowers Offered Nutrition, Oil, And Agricultural Versatility

With towering stalks and nutrient-rich seeds, they provided more than beauty. Tribes like Mandan and Hidatsa crushed seeds for oil, added them to baked goods, or ate them raw for energy. Beyond food, their sturdy stems were building materials, and their bright petals held spiritual symbolism.