History

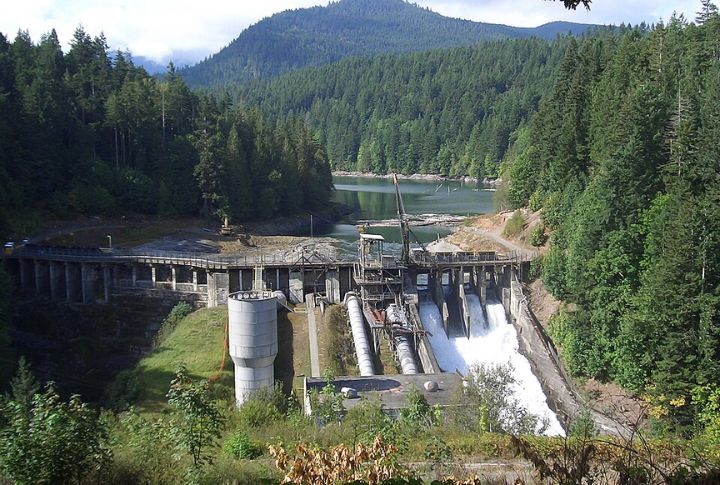

10 Good Reasons U.S. Communities Are Taking Down Old Dams

The thrum of roaring water and the thrill of reservoir boating are moments defining what many love about dams. Yet, underneath their massive facades lie buried toxins and rising flood danger. Findings from agencies like the USGS are now unraveling such long-term costs. Let’s explore the science pushing dam removals forward and what those changes might mean for residents.

Sediment Data Prompts Urgent Policy Shifts

Scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey found that sediment buildup behind older dams leads to water contamination and flood amplification. Buried metals and aging spillways also form a dangerous mix. These insights are driving local and federal authorities to reassess hundreds of existing structures across the country.

Fish Highways Are Reopening

Dams once blocked key spawning routes and stopped fish migrations cold. After removals on Maine’s Penobscot River, river herring are returning by hundreds of thousands each year. Atlantic salmon rebounded, too, rising from 248 in 2014 to over 1,500 in 2023. Reopened waterways then renewed fragile fish populations mile by mile.

Rivers Breathe Easier With Better Water Quality

Following the Elwha Dam’s removal, oxygen levels rose, and decades of industrial toxins were flushed downstream. Data reveals that stagnant water trapped behind dams can overheat and encourage harmful algae. On the other hand, free-flowing rivers restore chemical balance. This gives both wildlife and communities access to healthier water.

Indigenous Science Leads River Revivals

The Yurok and Karuk tribes, partnering with hydrologists, led the charge to dismantle four Klamath River dams. Their ecological knowledge, combined with aquatic biology findings, created a model of collaborative restoration. Then, cultural rights and science joined forces, and today, juvenile salmon are returning to sacred spawning grounds.

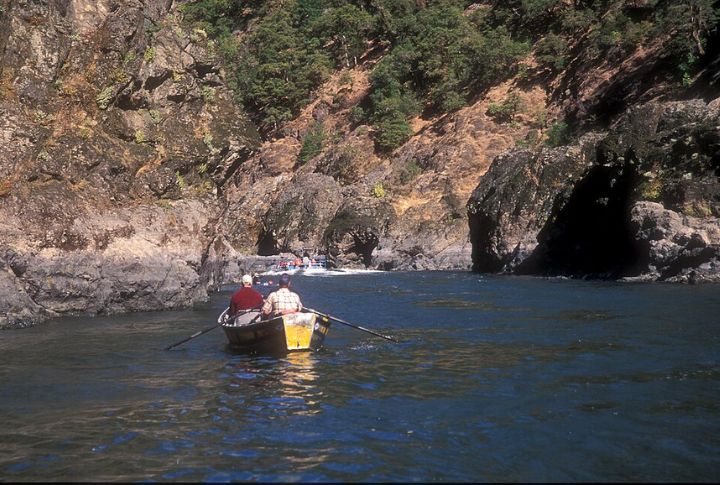

Recreation Improves After Dam Removals, Data Confirms

Rafting and kayaking have expanded on rivers like the Elwha, Klamath, and Rogue, where dam removals restored swift currents and natural rapids. Case studies by American Rivers and the U.S. Forest Service show that river recreation often surges post-removal, boosting rural economies and expanding access for paddlers, anglers, and nature-seekers alike.

Decaying Dams Pose Financial And Physical Risks

Experts at the Association of State Dam Safety report over 2,300 U.S. dams in poor or unsatisfactory condition, many built before 1960. Cracked spillways and outdated engineering threaten downstream towns. Rather than sink funds into repairs, officials increasingly turn to controlled demolition backed by engineering assessments.

More Species Are Returning Faster Than You’d Expect

After California’s San Clemente Dam was removed, species like steelhead trout, Pacific lamprey, and California red-legged frogs were documented returning to the restored corridor. Birds and other wildlife likely benefited, too, and this illustrates how habitat restoration sparks quick ecological response even if full tallies remain ongoing.

Climate Scientists Back River Restoration For Resilience

Oregon State University hydrologists argue that dam-free rivers buffer drought and flood cycles by restoring seasonal flow rhythms. Where channels once stagnated, reintroduced bends now absorb and release water naturally. These conclusions add fuel to the push for dam removals, especially in regions facing water extremes.

Cost-Benefit Analysis Favors Removal Over Repairs

While the Klamath River dam removal carries a projected cost of $450 million, it avoids extensive long-term maintenance and infrastructure upgrades. Additional benefits, like revitalized fisheries and tourism, are projected to add economic value, with some estimates reaching $150 million annually in related ecosystem services.

Social Science Tracks Emotional Benefits Of River Renewal

Where dams once stood, communities are now building trails, hosting festivals, or creating riverside classrooms. Restored waterways tend to boost engagement and foster a stronger sense of place. This is because, as rivers flow again, they often draw people back. They are reviving not just ecosystems but also civic pride and social connection.