News

20 American Trees At Risk Of Disappearing Forever

America’s forests are living archives of history, culture, and biodiversity. But these guardians of our ecosystems are facing quiet extinction. Many tree species are disappearing at a rate faster than most realize. Here, we take a closer look at those we stand to lose and why it matters.

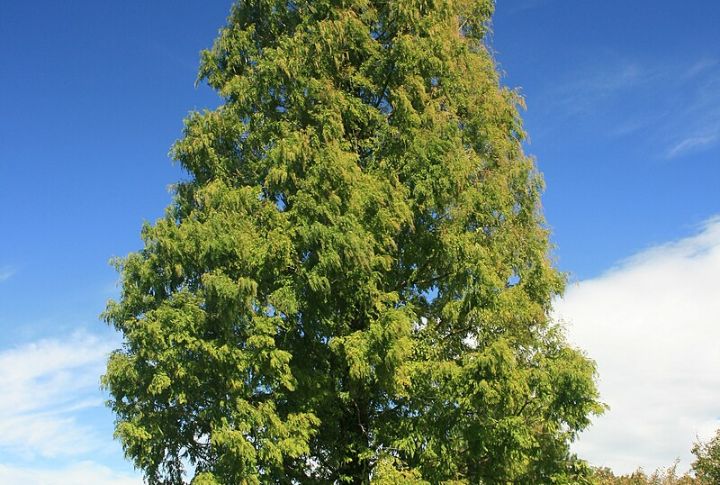

Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

The hemlock woolly adelgid, an aphid-like pest, is rapidly devastating hemlock forests across the eastern U.S. By feeding on the tree’s sap, it slowly kills these evergreens, leaving once-thriving woodlands eerily silent. As hemlocks play a key role in supporting entire ecosystems, their decline poses a serious, cascading threat to biodiversity.

American Beech (Fagus grandifolia)

Recognizable by its smooth gray bark, the American beech is under siege from beech bark disease, which is caused by fungi introduced by scale insects. It weakens and eventually kills mature trees, threatening both the beech species and the wildlife that depend on its nuts.

Florida Torreya (Torreya taxifolia)

Critically endangered, this rare conifer clings to survival in northern Florida and southern Georgia, with only a few hundred wild individuals remaining. Fungal diseases, habitat degradation, and climate shifts have pushed it to the edge. Botanists are racing to propagate saplings before their numbers dwindle further, thereby impacting biodiversity.

Santa Cruz Cypress (Hesperocyparis abramsiana)

This cypress, found only in California’s Santa Cruz Mountains, is teetering on the brink because of land development and habitat fragmentation. With its population still critically low despite conservation efforts, it’s a race against time and suburban sprawl. Its loss would mean the extinction of a species found nowhere else on earth.

Bristlecone Pine (Pinus longaeva, Pinus aristata)

Some bristlecone pines have stood for over 5,000 years in high elevations of the western U.S. Almost like you’d expect from human aging, they’ve become less resilient with time, mostly due to climate change making them more vulnerable to pests that were previously kept at bay by cold.

Bishop Pine (Pinus muricata)

The Bishop Pine prefers the foggy, fire-prone ridges of its limited coastal California range. However, this limited range, combined with fragmented populations, makes it vulnerable to habitat loss and climate change. It’s a fire-adapted tree, but too-frequent or intense blazes, along with encroaching development, are overwhelming its ability to regenerate

Cuyamaca Cypress (Hesperocyparis stephensonii)

Found exclusively in a small area of Southern California’s Cuyamaca Mountains, this tree’s entire known habitat was nearly erased by wildfires in the early 2000s. Recovery has been slow, and fewer than 50 mature ones remain in the wild. With its extremely limited distribution, wildfires pose a significant threat.

Dawn Redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides)

There’s fossil evidence that dawn redwoods once thrived in North America. Although they were thought to be extinct, the species was rediscovered in China in the 1940s. They have been widely planted as ornamental trees in the U.S. but face threats from habitat loss and fragmentation.

Cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani)

Though not native to the U.S., the cedar of Lebanon is a cultural symbol and an ornamental tree here. In its Eastern Mediterranean homeland, centuries of logging, grazing, and climate shifts have worn away its range. Conservationists are now nurturing seedlings in protected forest reserves.

Chilean Monkey Puzzle (Araucaria araucana)

Spiny and architectural, this ancient tree is beloved in specialty American gardens. However, in its endemic habitat—the Andes mountains of Chile and Argentina—it’s endangered by land conversion and logging. It is also sacred to Indigenous Mapuche communities, so there is some added cultural significance to preservation efforts.

American Chestnut (Castanea dentata)

Once a dominant species in eastern U.S. forests, the American chestnut was devastated by invasive fungal blight in the early 1900s. All mature trees were eliminated, reducing the species to sprouting stumps. The American Chestnut Foundation has attempted to breed blight-resistant varieties through cross-breeding and genetic techniques in an effort to restore this iconic tree.

Whitebark Pine (Pinus albicaulis)

The whitebark pine is vital to high-mountain ecosystems. Seeds from this tree feed grizzly bears, and the tree itself stabilizes the soil. But white pine blister rust and warming temperatures are decimating its numbers. Now federally listed as threatened, it’s in urgent need of large-scale protection.

North American Ash (Fraxinus spp.)

The emerald ash borer is a metallic green beetle from Asia that is tearing through ash forests at a shocking pace. This unprecedented attack is already causing economic impacts from the loss of valuable timber. Whether green, white, or black ash, these trees won’t survive the borer without human intervention.

Florida Yew (Taxus floridana)

This yew species is endangered, growing quietly in a tiny part of the Florida panhandle. Its population is confined to approximately 10 square miles. Shade-loving and fire-sensitive, it has little tolerance for changes in land use or natural disturbances. But its loss would eliminate a species with potential medicinal properties.

Butternut (Juglans cinerea)

Unlike its more resilient cousin, the black walnut, butternut populations are vanishing fast. Also known as white walnut, they are declining due to a fungal disease called butternut canker. Its decline affects biodiversity and the availability of its nuts, which are a food source for wildlife.

American Elm (Ulmus americana)

The American elm was once a common towering icon of city streets and countryside groves. It has since been severely impacted by Dutch elm disease, which has altered urban landscapes and forest ecosystems. Although some resistant strains are being developed, the threat still looms large across much of its range.

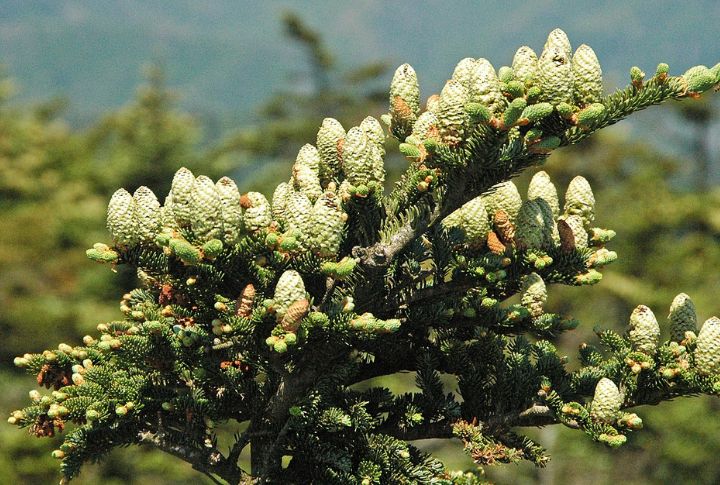

Fraser Fir (Abies fraseri)

Not many know that this famous holiday tree serves a higher purpose than decor. Fraser firs also anchor fragile mountain ecosystems. No thanks to the balsam woolly adelgid, mature trees have declined, especially in the Great Smoky Mountains. Regrowth efforts are underway, but it’s an uphill climb.

Longleaf Pine (Pinus palustris)

These towering trees once covered 90 million acres of the southeastern U.S. Now, only a fraction remains because of land development and agriculture. It becomes a chain reaction of problems because the Longleaf Pine supports endangered species like the red-cockaded woodpecker. However, there are ongoing replanting initiatives.

Coast Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens)

These giants are among the Earth’s tallest trees. But they seem to be no match still for climate-induced drought and fire threats. Despite their thick bark and longevity, recent wildfires and habitat fragmentation are pushing them into unfamiliar territory. Their loss would mean reduced carbon sequestration, further worsening climate change.

Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum)

Maple syrup fans, take note: sugar maples are facing threats from climate change, acid rain, and soil depletion. No maple tree, no maple syrup. Their loss across northeastern forests would be particularly painful because of the economic value they bring, including their brilliant autumn color that supports tourism industries.