Education

10 Parts Of The U.S. Quietly Slipping Into A Water Crisis

Water crisis stories usually focus on deserts, but that’s no longer the full picture. Across unexpected corners of the U.S., water is disappearing fast. Lakes shrink, wells dry up, and communities scramble for solutions. These ten regions show just how widespread and urgent the issue has become.

Ogallala Aquifer Region, Nebraska

Water loss in parts of Nebraska exceeds 50%, and aquifer recharge is a few times slower than usage. Farmers drill deeper than ever. In fact, some wells now need to be drilled twice as deep as 30 years ago. Corn and beef output now hinge on a vanishing resource once taken for granted.

Wasatch Front, Utah

The Great Salt Lake has lost two-thirds of its volume since 1986. Shrinking snowpack has further reduced Utah’s main water source, while growing development drains more from already stressed reservoirs. As the lake recedes, toxic dust blows from the exposed bed, and lake-effect snowstorms are fading into memory.

San Luis Valley, Colorado

Potato farmers are raising the alarm as underground aquifers run dry, forcing wells to shut down. With 75% of the region’s water going to agriculture, conditions are becoming critical. The state recently blocked a proposal to export water elsewhere, fearing it would push this already fragile valley closer to another Dust Bowl.

Klamath Basin, Oregon

Zero water allocations. That’s what many farmers now face. Endangered fish require more stream flow. Wildlife refuges dry out. Conflict escalates, and uncertainty spreads. Some landowners are giving up entirely, turning productive fields into dust-blown fallow stretches with no guarantees.

Central Texas Hill Country

Stage 4 drought rules are active across multiple towns. The Edwards Aquifer continues to hit historic lows. Austin and San Antonio expand, draining more supply, while cattle ranchers sell early to cut losses. Even bluebonnets—the state’s icon are vanishing from parched hillsides once covered in blooms.

Southern Illinois

This isn’t the Illinois that most people picture. U.S. Drought Monitor (2024) shows short-term precipitation deficits of 2–4 inches below normal, especially in spring and summer months. Even with irrigation, corn yields are slipping. Drier conditions are disrupting deer and waterfowl movements, making traditional hunting seasons less predictable and altering where wildlife can be found.

Rogue Valley, Oregon

In recent years, the snowpack has failed to deliver. As water sources fade, orchards and vineyards now fight for what remains. In dry months, homes depend on trucked-in supplies. Wildfire risk climbs, and even golf courses have replaced greens with drought-resistant grass varieties.

Southwestern Idaho

Boise just saw record-low rainfall last summer. The Snake River slows as snowpack fades and reservoirs drop. Counties also declared drought emergencies in 2024. Potato farms are hit the hardest. Landscaping norms are changing too, since lawns are disappearing as residents switch to water-saving xeriscaping designs.

Northern Georgia Foothills

Lake Lanier reached record lows in 2023, putting metro Atlanta’s water in jeopardy. State officials say this pattern may be permanent. Appalachian streams dry up sooner each year. Water use is now restricted as car washes, swimming pools, and even fishing trips are being curtailed.

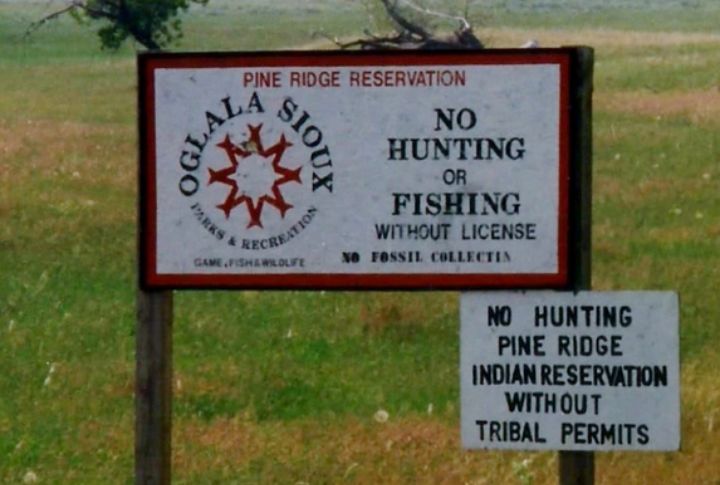

Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota

Drought in 2024 triggered emergency action on the Pine Ridge Reservation. With unsafe wells and little supply, families relied on water deliveries or hauled their own. Buffalo relocation underscored the severity. Tribal leaders call it a “crisis of sovereignty,” as basic needs and cultural ties are now under threat.