Washington

Inside The Making Of Washington, D.C. As The Capital

The capital of the United States didn’t land on the map by accident. It took bold decisions and long-term planning to turn an undeveloped patch of land into a seat of power. These choices and conflicts show what went into the making of Washington, D.C., as the nation’s capital.

Capital City Contenders

Before D.C., America tested a few contenders. New York served as the first capital; however, its northeastern location felt too dominant for many. Meanwhile, Annapolis and Trenton came under brief consideration, though neither quite measured up. As a result, the need for a neutral, unifying site quickly became a national priority.

The Retrocession Of Alexandria

In 1847, Washington, D.C., shrank when Alexandria was returned to Virginia through retrocession. Residents pushed for the change, frustrated by federal neglect and concerned about slavery’s future. The move reversed earlier territorial planning and highlighted tensions between local interests and national priorities in shaping the capital’s evolving size and identity.

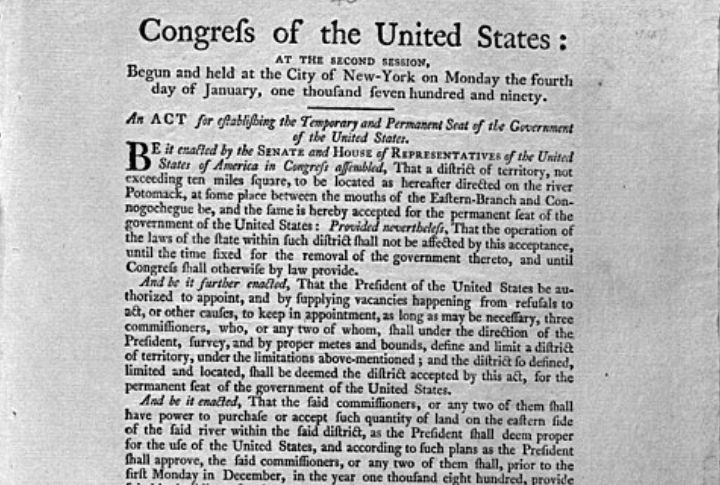

The Residence Act

Enacted in 1790, the Residence Act authorized a federal district along the Potomac River and reflected a political bargain. Southerners gained the capital’s location, while Northerners won federal help paying state debts. The law designated Philadelphia as the temporary seat and allowed President Washington to appoint commissioners to oversee the design and construction of D.C.

Washington’s Personal Choice

George Washington didn’t leave the capital’s location to chance—he selected the exact ten-mile square along the Potomac himself. The site’s closeness to Mount Vernon and its position between North and South made it an ideal choice. He approved the land cession from Maryland and Virginia, giving the project national character and lasting legitimacy.

Potomac River Strategy

The Potomac checked every box—navigable waters, access to the Ohio River system, and a midpoint between North and South. Its fresh water and high ground made it ideal for settlement and defense. Washington recognized its long-term potential and backed the site as a future economic and transportation corridor for the growing nation.

L’Enfant’s Grand Plan

French engineer Pierre L’Enfant designed more than a city—he envisioned a statement of national identity. His layout included broad boulevards and diagonal avenues that converged on major civic landmarks like the Capitol and White House, and open spaces reflected Enlightenment ideals. Though dismissed before finishing the job, much of his original design endured.

Banneker’s Survey Legacy

In 1791, Benjamin Banneker joined the team surveying the new capital. A free Black astronomer, he helped place boundary markers and used celestial readings to verify the site with remarkable precision. After a dispute led to lost plans, he reportedly recreated L’Enfant’s design from memory. His role stood out in a time of widespread exclusion from science.

Slavery And Construction

Skilled hands built the Capitol and the White House, but many of those hands were enslaved. Hired out by their owners, Black laborers shaped the core of the new republic. The irony was striking: freedom memorialized in marble, constructed by those denied it. That legacy still shapes how the capital’s story is remembered today.

The 1814 Invasion

It didn’t take long for Washington, D.C., to face destruction. British forces entered during the 1812 conflict and set federal buildings ablaze. Then nature stepped in—a sudden storm, possibly a tornado, put out the fires and scattered the enemy. The capital survived, scarred but not defeated.

Why It’s Not A State

From the start, D.C. was designed to stand apart. The Constitution placed it under Congress alone, without ties to any state. Federalist No. 43 spelled out the logic—neutrality over influence. This arrangement ensured that the nation’s capital would remain neutral ground, free from the control or influence of any single state.