News

10 Ways Canyon De Chelly Helps The Navajo Maintain Their Way Of Life

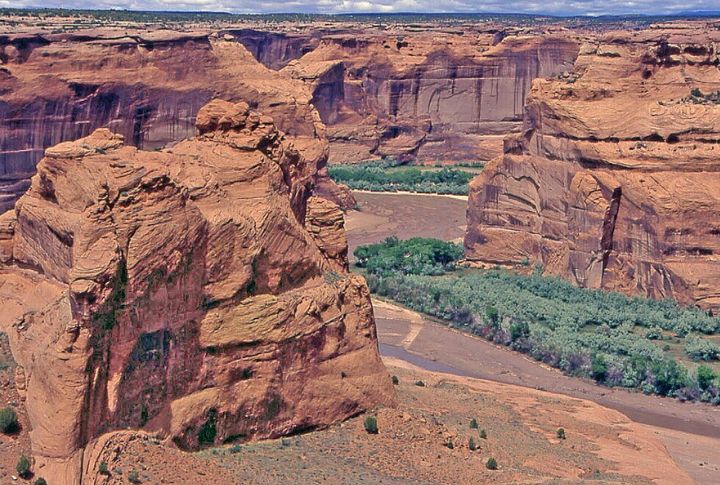

In the red rock heart of northeastern Arizona, Canyon De Chelly stands as a lasting chapter of Navajo history. Generations have sheltered and passed down traditions within its walls. The cliffs offered protection, and the land kept culture alive. Explore how this remarkable canyon became a stronghold of identity and tradition for the Navajo people across centuries.

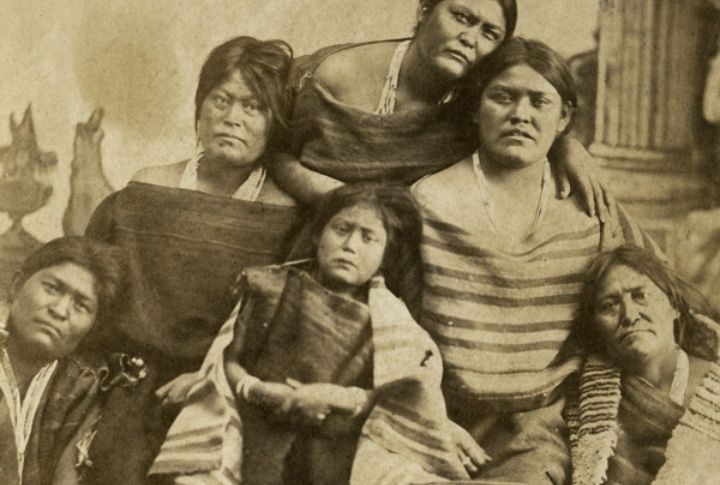

Natural Fortification Shielded The Navajo From Invaders

The canyon’s steep sandstone walls formed a rugged barrier that foreign troops struggled to penetrate. During Kit Carson’s scorched-earth campaign in the 1860s, Navajo families found refuge in high alcoves. This natural defense system became a natural stronghold, not just a backdrop.

Sacred Ceremonies Found A Home Within The Canyon Walls

Beyond its sheer cliffs and shadowed groves, Canyon De Chelly holds spiritual meaning. Navajo medicine men performed ceremonies tied to healing, harmony, and balance in secluded spaces. The continuity of ritual here represents an unbroken thread, linking modern Navajo spirituality to its ancient ceremonial environment.

Traditional Agriculture Thrived In The Fertile Canyon Floor

Unlike the surrounding desert, the canyon’s alluvial soil and stream-fed fields allowed consistent farming. Families cultivated staple crops and passed down irrigation techniques suited to the land’s natural contours. This agricultural legacy supports both physical survival and a deeper cultural relationship with place and season.

Rock Art Preserved Ancestral Narratives And Teachings

From stylized animals to symbolic figures, the canyon walls read like a permanent archive. Petroglyphs and pictographs reflect ceremonial knowledge and survival practices. These artworks weren’t decorative—they formed a collective memory system, blending visual storytelling with cultural education long before written records emerged.

Storytelling Traditions Took Root In The Canyon’s Silence

Quiet nights in the canyon amplified the voices of elders recounting origin stories, clan journeys, and moral parables. The physical surroundings often appeared in the narratives themselves. Rather than fading with time, these oral traditions took a stronger hold and connected younger generations to place and lineage.

Seasonal Herding Preserved A Self-Sufficient Lifestyle

Each spring and fall, Navajo herders moved sheep and goats between the canyon floor and its rim. This pattern sustained families economically without dependence on external systems. Wool and milk were integrated into ceremonial life, which reinforced ties between seasonal movement and cultural responsibility.

Clan-Based Land Use Strengthened Community Bond

Rather than private ownership, land in Canyon De Chelly was allocated by clan ties and ancestral claims. This approach kept families rooted in specific plots and encouraged generational stewardship. Kinship shaped land use decisions and created a landscape where governance emerged from tradition, not bureaucracy or force.

Navajo Artisanship Drew Inspiration From Canyon Surroundings

The textures, colors, and forms of the canyon directly influenced Navajo creative work. Weavers matched sandstone hues in rugs; silversmiths etched designs echoing canyon geometry. Artistic practices mirrored environmental cues and linked creative expression with reverence for the land that shaped it.

Federal Recognition Protected Customary Use Of The Land

Unlike other national parks, Canyon De Chelly is owned by the Navajo Nation and co-managed with the National Park Service. This unique agreement, formalized in 1931, preserved rights for Navajo families to farm and live within the canyon while resisting outside cultural displacement.

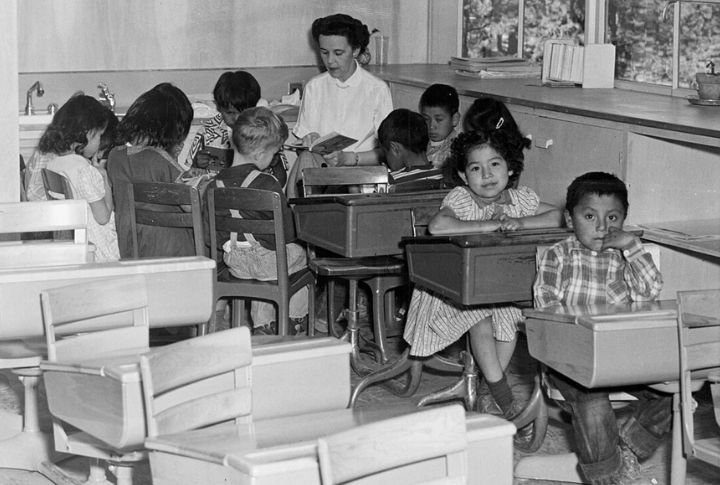

Canyon Schools Supported Language And Cultural Revival

Education within and near the canyon has shifted toward preserving the Navajo language and worldview. Immersion programs and community-based curricula reconnect youth to a culture that earlier boarding schools aimed to erase. In these schools, the canyon becomes more than a location—it becomes part of the lesson.