History

The Untold Stories Behind Iconic American Photographs

There’s something grounding about 19th-century photographs. You’re looking at people who never thought they’d be remembered, places caught before they were paved over, and events that shaped entire generations. These images weren’t filtered or posed—they just happened. And in that rawness, they reveal a side of America that textbooks tend to miss.

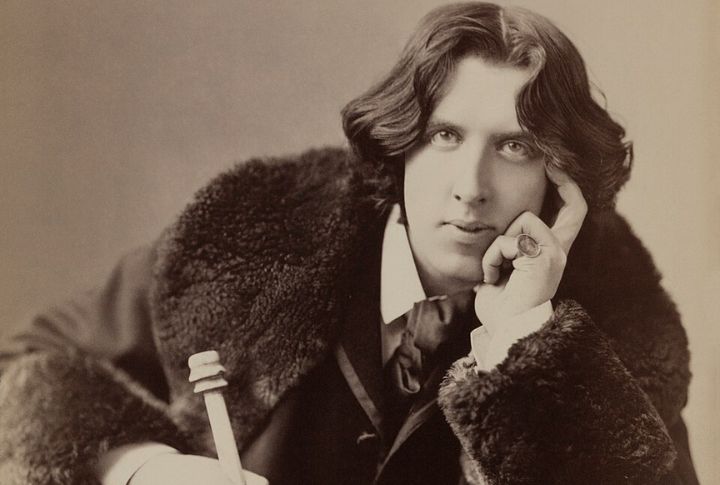

1843: President John Quincy Adams

Adams didn’t care for the result, calling it “hideous,” but the daguerreotype by Philip Haas is the oldest known photo of any U.S. president. He was 76, sharp as ever, and still serving in Congress. Today, the image hangs in the National Portrait Gallery, a ghostly record of a founding-era figure.

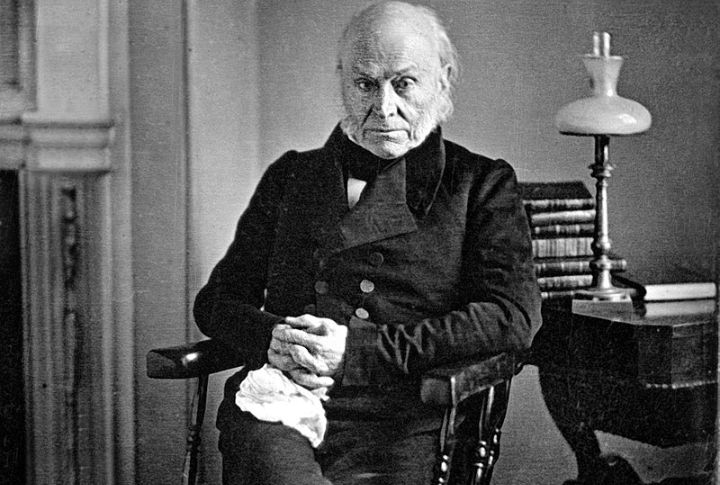

1846: The White House

Before the columns and crowds became familiar symbols, John Plumbe Jr. captured the Executive Mansion as it looked in Polk’s presidency—unpolished, half-shadowed, and remarkably quiet. It’s less about power and more about a place still finding its identity. It’s a rare architectural portrait before the expansions and the fences.

1848: Dolley Madison And Niece

Dolley had long outlived the White House parties by the time she sat for Mathew Brady with her niece, Anna Payne. She was frail but still held the poise of Washington’s grand dame. Taken a year before her death, the portrait carries the air of a woman who understood legacy.

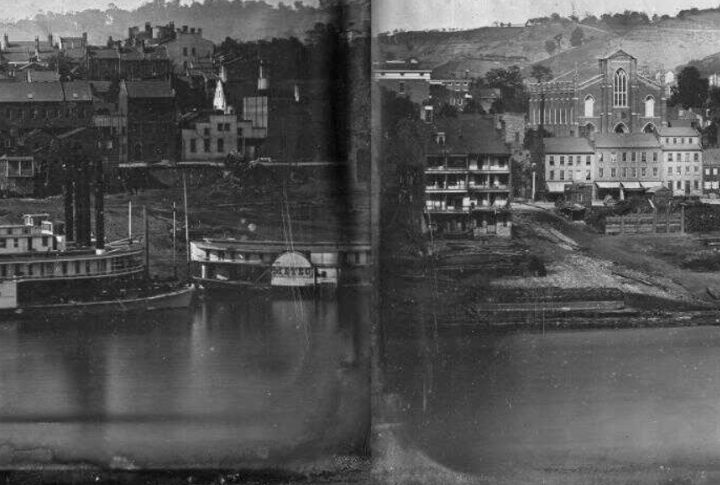

1848: Cincinnati’s Waterfront Panorama

This isn’t just a photo—it’s an industrial mural. Taken by Fontayne and Porter, the 1848 panorama shows Cincinnati on the brink of becoming a Midwest hub. Steamboats crowd the Ohio River, warehouses bustle, and smokestacks slice the sky. It’s commerce and American ambition all pressed into silver.

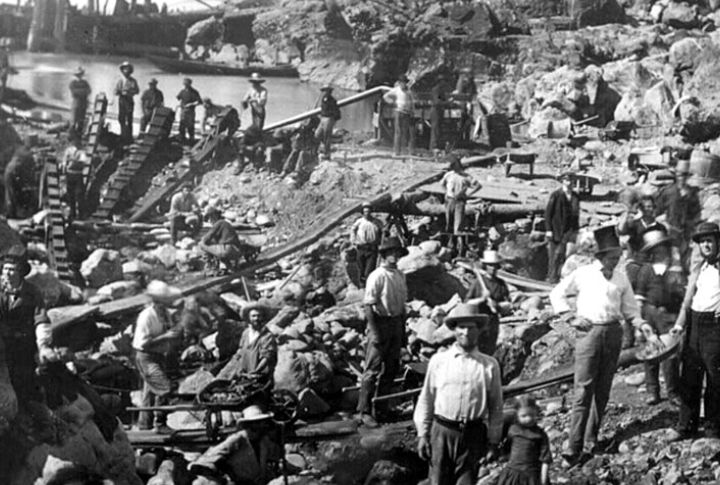

1852: Gold Miners At Spanish Flat

No gold bars here, just muddy boots and frozen fingers. This image of Spanish Flat miners reminds us that the Gold Rush was less about riches and more about survival. You can almost feel the cold creek water and the weight of hope. It’s a snapshot of labor and fleeting luck.

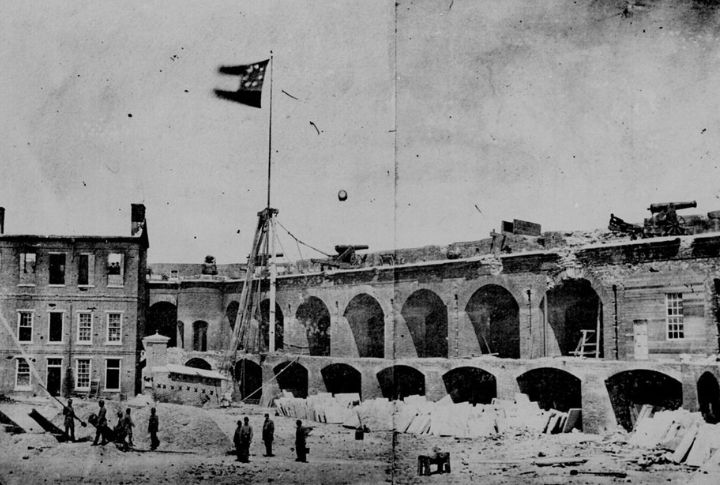

1861: Confederate Flag Raised At Fort Sumter

After 34 hours of shelling, the Union surrendered Fort Sumter. What came next was symbolic and sobering: a photo of the Confederate flag rising where the stars and stripes had flown. It marked the moment the Civil War wasn’t just talk anymore. It was a violent, irreversible break.

1862: Campbell General Hospital, Washington, D.C.

In this photo, the rows of tents and wooden wards stretch beyond what seems possible. Campbell Hospital was massive, and it had to be. The stars on the flag include every state, even those in rebellion—a quiet refusal to let the Union crack. Inside, medicine was brutal but evolving.

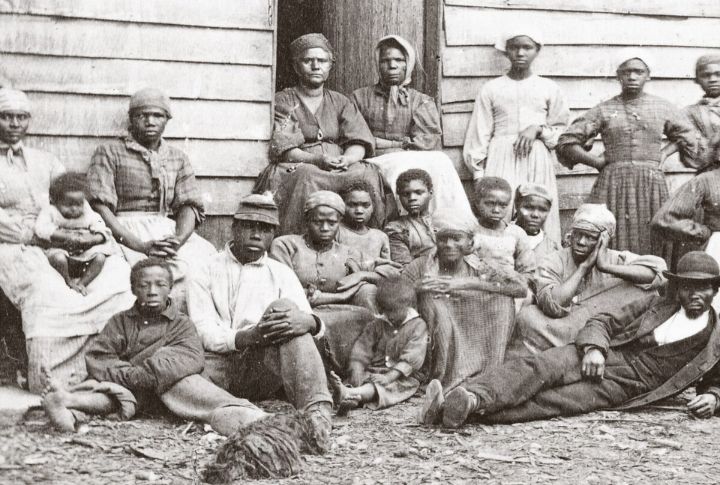

1862: Freed People In Virginia

They were labeled “contraband,” but that didn’t stop them from walking toward freedom. Captured in 1862, this image shows recently emancipated people, some barefoot, some clutching children, lingering near Union troops. They weren’t yet citizens, but they’d left enslavement behind. The photograph is heavy with exhaustion and the beginnings of hope.

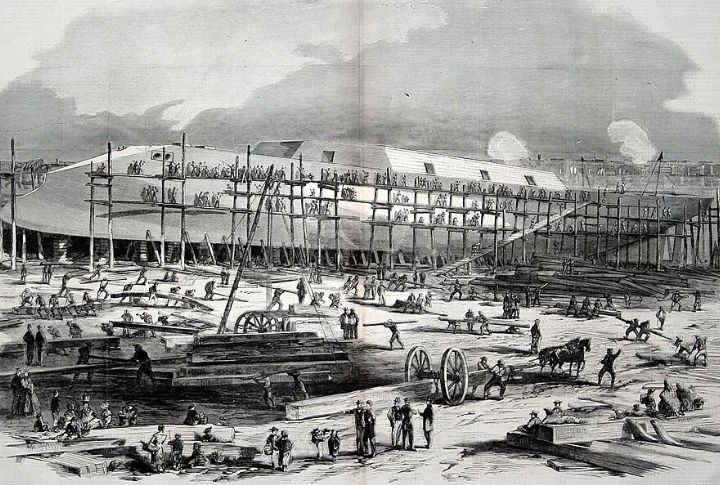

1863: USS Dunderberg In Webb Shipyard

This is not a story of romance but one of pure industrial power. William H. Webb’s shipyard launched some of the most ambitious vessels of the era, including the Dunderberg. It stood as the largest wooden ship ever built, and it looked like it could crush anything in its path. In 1863, it practically defined naval innovation.

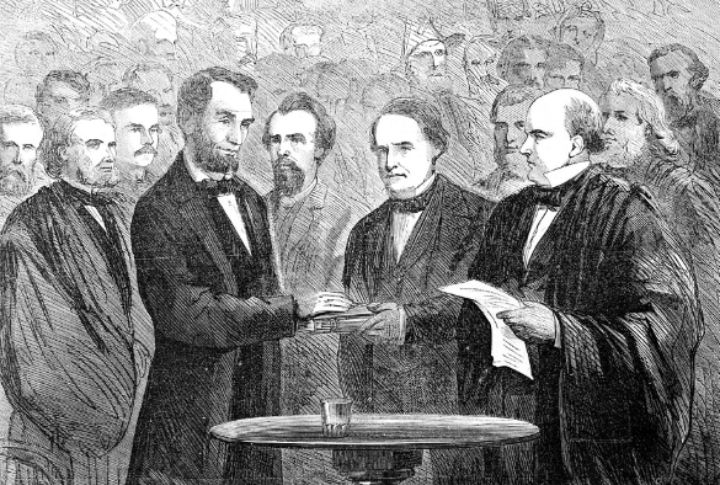

1865: Lincoln’s Second Inauguration

The photo is grainy, but Lincoln is there, almost lost in a sea of top hats and expectations. His second inaugural was less of a victory lap and more of a sermon. Slavery, sacrifice, and reconciliation were all in his voice. The war was ending, and he was trying to stitch the wound before it scarred too deep.

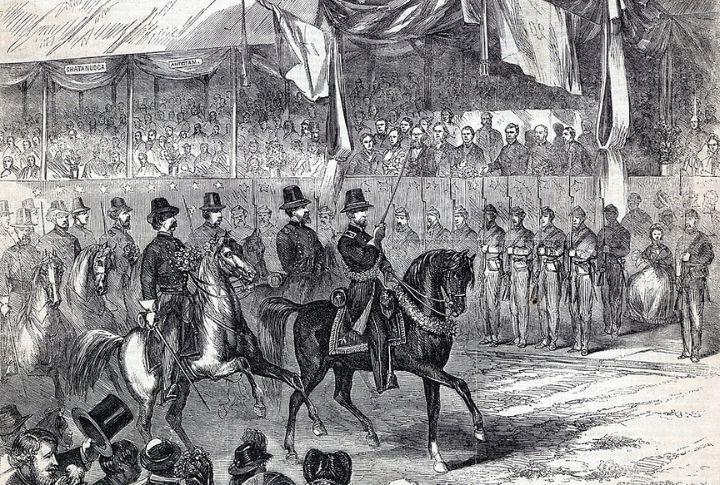

1865: Grand Review Of The Armies

The Union soldiers marched by the tens of thousands down Pennsylvania Avenue. The feeling in the air was not only triumph but deep release. After years of bloodshed and hardship, the Grand Review let a weary nation finally exhale. The photo hums with quiet pride.

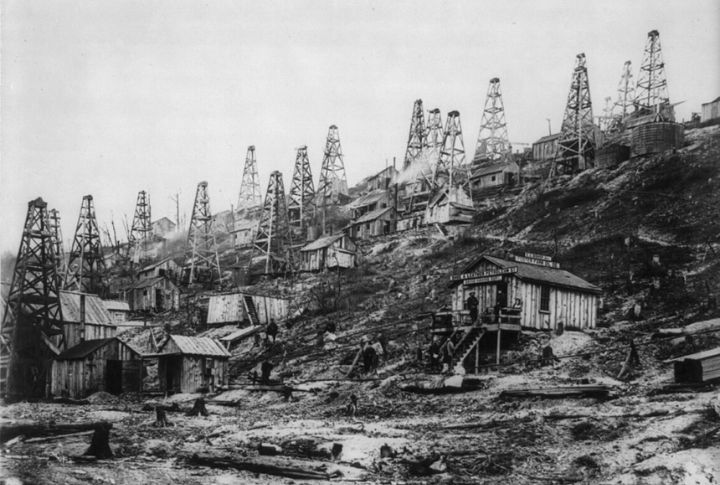

1865: Pioneer Run Oil Field

Titusville’s forests were gone, replaced by derricks and drums. The oil boom looked chaotic—mud, smoke, leaking barrels—but it fueled everything from lamps to locomotives. This photo of Pioneer Run captures the moment America shifted from wood and water to something darker and more combustible. It was the start of energy dominance.

1867: Main Street, Salt Lake City

It had no glamour, only grit. Main Street in 1867 stretched across dust and wagons, lined with rough wood-frame buildings, all set against mountains and the weight of religious ambition. Mormon settlers worked to carve permanence in an unforgiving land. The photo shows the bare bones of a future capital.

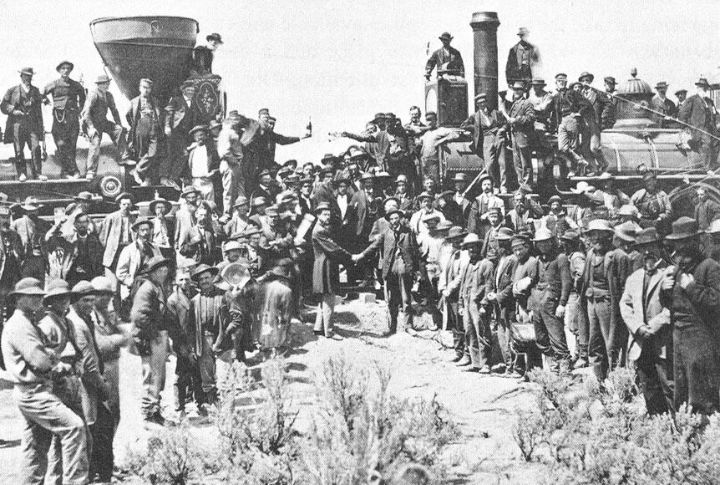

1869: The Golden Spike At Promontory

On May 10, 1869, a golden spike met the rail, closing the gap between the two coasts. In the photograph, workers and onlookers lean in, aware they are part of something bigger. It marked a turning point that would pull the nation closer together.

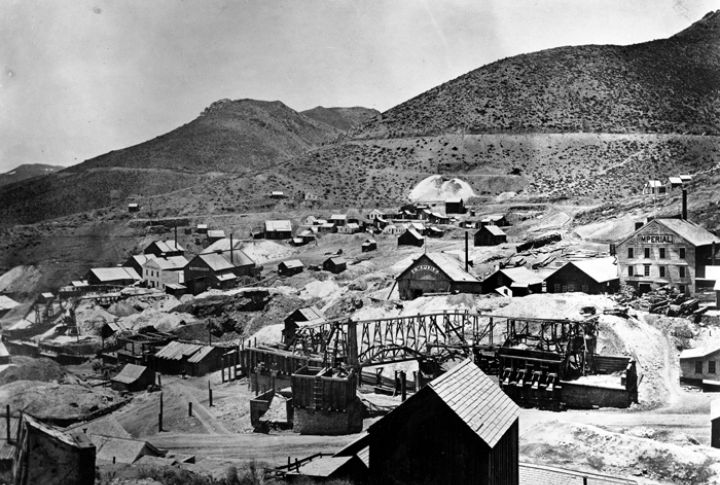

1870: Virginia City, Nevada

By 1870, Virginia City had erupted into a boomtown fueled by silver fever. The wide roads and ornate buildings in the photo hint at success, but volatility simmered underneath. Fortune chasers lived on a knife’s edge, where prosperity could turn into disaster overnight.

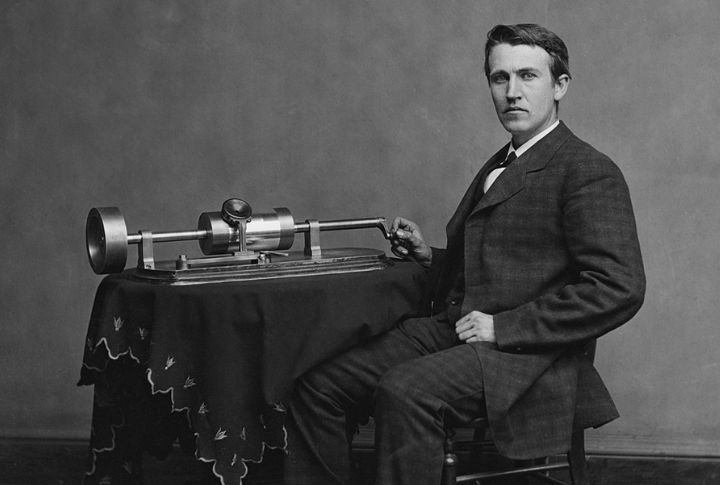

1871: Thomas Edison’s First Experiments

There’s something unsettling in young Edison’s eyes. Taken around the time of his marriage to Mary Stilwell in 1871, this photo hints at the frenzy to come. His early work on the phonograph wouldn’t begin until 1877, but he was already sleeping in labs and scribbling into the night.

1875: Brooklyn Bridge Rising

The Brooklyn Bridge wasn’t finished in 1875, but its towering presence told the story. Rising high above a clutter of ferries and factories, they promised connection and undeniable power. Even without the cables, the shape of modern New York was steadily coming into focus.

1876: Liberty’s Torch At The Centennial Fair

The Statue of Liberty’s arm made a dramatic debut at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, even though the statue wasn’t finished. Visitors could climb into the torch for 50 cents, a clever blend of spectacle and fundraising that introduced the country to liberty’s symbol.

1880s: Rockefeller Walks Past A Beggar

In an era defined by opulence, the photo of John D. Rockefeller ignoring a street beggar became a quiet indictment. Critics would use it as a symbol of unchecked capitalism and inequality. Rockefeller would later become one of the country’s greatest philanthropists, but this moment spoke louder than any donation.

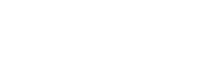

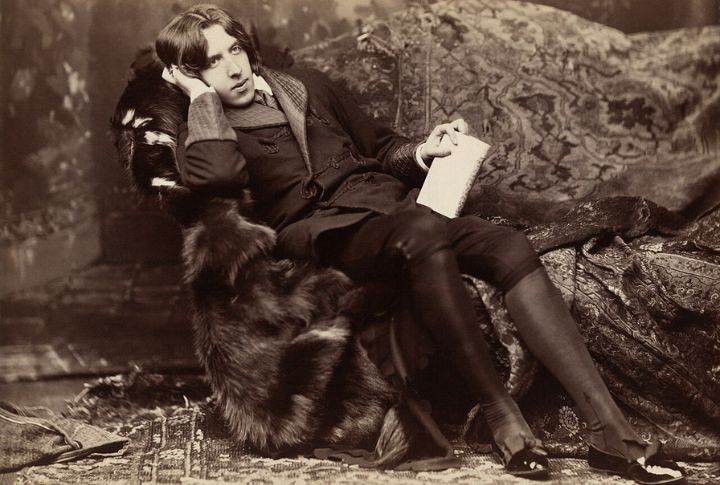

1882: Oscar Wilde In Silk And Velvet

No one understood this image better than Wilde. In 1882, he toured America with his wit and wardrobe, and Sarony’s photo of him in velvet breeches turned into a collectible. It wasn’t just a portrait—it was marketing. Wilde knew how to dress for a camera before most people even knew what one was.